I’ve always enjoyed working with my hands, and in college I took classes in jewelry and metals. I was taught by a Professor named David Peterson who is an extremely talented (albeit tough) teacher. After studying with David for two or three semesters, I realized that I had never seen anything that he himself created, so one day a few students and I convinced him to bring some of his work to class. He brought in one piece – it was a salt and pepper shaker (I found a picture here in David’s now-online portfolio). I still remember when I saw it for the first time, it was one of the most creative, interesting, and impressive works of art I’ve ever seen.

After he showed us the piece, he took out a very large piece of blueprint paper and showed us his draft drawings. Holy moly – his drawings were so detailed and intricate that they themselves were a work of art. He had completed detailed scale drawings of every single component of the piece in immaculate detail.

When I saw the drawings, I couldn’t help but thinking how much time the drawings must have taken. Hours, days probably. At the naïve age of 20, looking at those drawings, I remember having only one thought:

“What a waste of time!”

In college, when I worked in jewelry, I never spent a long time planning. I would get a general idea, maybe do a quick sketch in a small sketch book, then just sit down at the bench and start sawing and soldering until I got results that I was happy with.

“Dive right in”

It was the method that I used for a lot of projects in a lot of areas.

Looking back – I now understand why David spent so much time drawing out his creations. But the lesson took me a very long time to learn. Here’s why: I often got good results by just diving in!

For less complex projects, I could usually get acceptable results by just sitting down and working. And I got those results faster than I would have if I’d spent a lot of time drafting out a solution.

Drafting a solution is slow painful work. It involves taking careful measurements to accurately define the problem, evaluating every aspect of the project, and then re-creating a scale representation of the solution on paper. Drafting is really an art unto itself.

Over time I learned, the more complex the project, the less likely I was to get an acceptable result by just diving in. At a certain point, my rate of success approached zero and I would end up spending 10x more time fixing mistakes than I would have if I had just done the necessary drafting work up front.

For instance, on a project with the level of complexity of David’s salt and pepper shaker – there’s no way anyone could get anything close to an acceptable result without very careful planning.

There’s an interesting corollary here to work in an office environment.

In the corporate world, young people often get promoted quickly for being the most eager to jump in and do things. That eagerness, combined with a talented person and a task of low or medium complexity, often produces good results quickly.

Those good results create a positive feedback loop. The young eager person gets promoted and put in charge of even larger and more complex tasks. But that cycle is broken when the tasks ascend to a degree of complexity where the “dive in” method does not yield a very good chance of success. Ultimately those same young people who were promoted the fastest find themselves stuck in the middle of the corporate ladder without the “drafting” skills they need to design and plan larger operations.

To succeed at senior management levels, you need a different set of skills. Even on a project with a high level of time pressure, rather than diving right in, you first need to take measurements and draft a solution.

Succeeding in complex endeavors is about having the skill to be a draftsperson and about having the discipline to spend the time drafting.

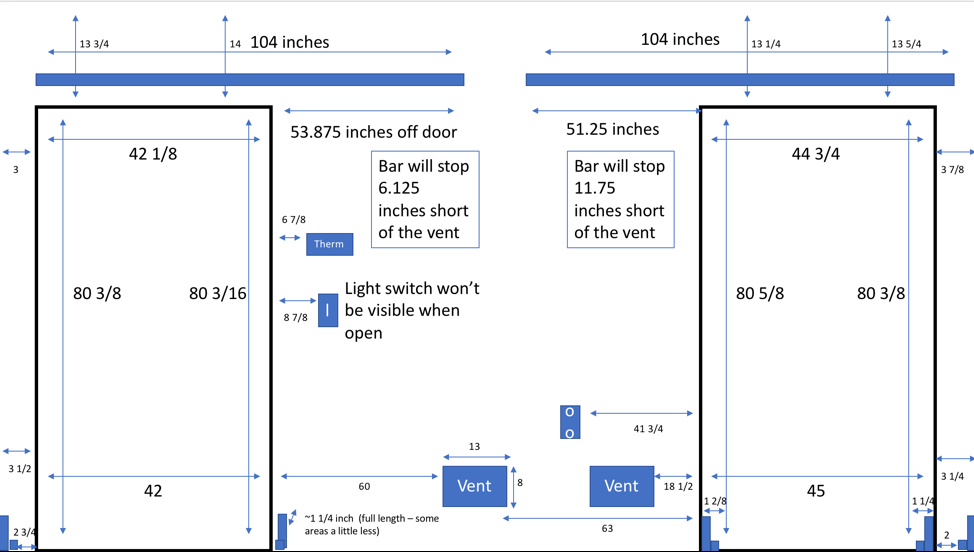

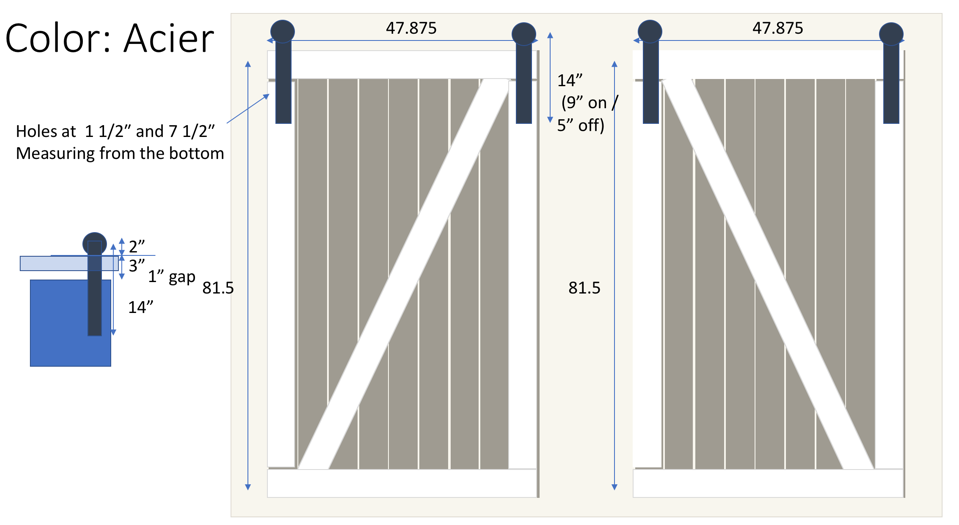

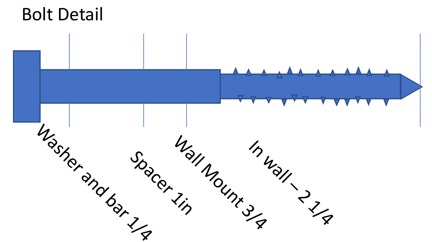

I recently took this lesson to heart when working on the barn door project for our living room. Contrary to the “dive in” method i favored in college, for this project I planned out every detail (see below for some of the plans).

Although the project took 3 months, I think the results speak for themselves.