Those of you who know me, or those of you who have been curious enough to click on the “Jewelry Portfolio” button in the upper right of this website, know that I’m a hobbyist metalsmith. I studied metalsmithing in college and make about 10-15 pieces per year – mostly rings, either wedding rings for friends or presents for my wife.

I order my materials (silver, gold, platinum, etc.) from a metals distributor (effectively a metals mill) and make the pieces by hand in studio we have in the basement of our house.

The mill I work with supplies many larger jewelry stores and last week they sent me a solicitation to sell their pre-made jewelry.

According to the solicitation, I would pay them about $10,000 upfront, and they would send me 12 rings that I could re-sell to my customers for $50,000, turning a $40,000 profit.

Their economic proposition was solid, but I could not have been more offended.

I am a jeweler! I make all of my jewelry by hand; I’m not going to re-sell some mass-produced stuff, that’s not why I got into jewelry in the first place!

The more I thought about the solicitation, the more I wondered how many jewelers ended up taking the deal and sacrificing their craft for the sake of making a better profit. In order to understand that, we need to talk a little bit about the process of making jewelry.

Here’s where the fun starts.

There are many different ways to make jewelry and they each involve slightly different division of labor between the jeweler and the mill – and as a result, a different level of “handmade-ness”.

Method 1: Casting Grain

My favorite way to make a ring, and by far the most “pure” in terms of being handmade, is by ordering casting grain (effectively small metal balls) from the mill, melting them down into an ingot mold, and then hammering, cutting, drawing, and soldering the metal into the desired shape.

Ordering casting grain is also the most cost-effective way to order metal because it involves the least amount of processing at the mill. To give you an idea of the cost, five pennyweights (abbreviated “dwt”; about 5/18ths of an oz) of 14 karat yellow gold (just about what you’d need to make an average size ring) costs about $210. Of that $210, $197 is the raw cost of the gold based on fluctuating metal markets, and $13 is the fee paid to the mill for creating the product. That’s about a 6% fee – which is pretty good! At higher volumes the fee is even lower (as low as 1% once you get to ~$10,000 or above in order volume).

However, the part that’s not so good is the amount of labor involved in melting, forging and craft gold from scratch. It takes me about 10 hours of work to make one ring using this method. Needless to say, the business doesn’t scale too well if I can only make one ring per 10-hour day.

Method 2: Sizing Wire

The next more “pure” way to make a ring is by ordering what’s called “sizing wire” from the mill. Sizing wire is casting grain that the mill has already melted down and drawn into the dimensions you want. It comes in the form of a long wire – all you have to do is cut and form it.

If I was to order sizing wire to make the exact same ring as we contemplated in Method 1 above, it would cost about $216 for the materials. The mill charges an extra $6 for creating the wire. That brings the total fee to $19 or about 9% of the $216 total cost.

Yes – on a percentage basis, this is an increased fee (9% for the wire vs. 6% for casting grain), but it’s only $6 more and starting with the pre-made sizing wire vs. melting the gold yourself saves about two hours of labor. If you’re looking to start a business, this is a no brainer. $6 for two hours is an easy trade.

Because of the time savings I end up ordering a lot of sizing wire and still feel pretty good about still calling my work “handmade” – after all, I did all the work of cutting, sizing, finishing, and setting stones and it still takes a really long time.

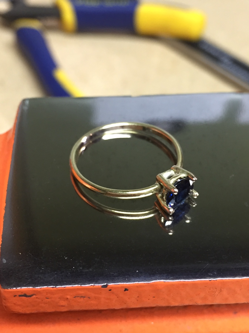

Here’s a picture of a ring I made last year from sizing wire:

(Ring: 1ct Sapphire set in 14kt Yellow Gold).

It took me about 8 hours to make this ring from start to finish.

Method 3: Pre-Fabricated Setting and Shank

By far the most labor intense part of making the Sapphire ring above was hand-crafting the setting for the stone (the wire prongs that hold the stone in place). Each prong of the basket setting had to be soldered independently and carefully as to not disrupt the position of the other prongs. The size of the setting also had to match the size of the stone perfectly, or else the stone wouldn’t fit correctly. The setting alone took about four hours to make (half the time of the total ring).

The mill knows that creating settings is a very time-consuming activity – so they actually sell pre-fabricated stone settings. Something like the picture below:

For about $30 ($22 material/$8 fee) I could have ordered a pre-fabricated stone setting for this ring. The fee on the pre-fab setting is pretty hefty at 27% – but hell, it would have saved me four hours of work and it’s only an extra $8. A lot of jewelers probably see this as an easy trade as well.

Well – now that I’m ordered the pre-fab stone setting, what about the ring “shank” (the part that goes around your finger)?

As it turns out, I can also order a pre-fabricated shank that fits this setting perfectly for about $225 ($194 materials/$31 = 14% fee).

The total I would have to pay for the pre-fabricated shank and setting would be $225 + $30 = $255.

When ordering a pre-fabricated shank and setting – there is only one soldering step to create the ring (just attach the setting to the shank and you’re good to go) – that would probably only take about two hours of work total to get to a finished ring (down from 10 hours of work in method 1). That’s eight hours of time savings for an incremental fee of 17% pts.

Here’s a quick table to summarize so far:

| Time to make 1 ring | Total Cost | Cost Material | Fee | % Fee | |

| Method 1: Casting Grain | 10 Hrs | $210 | $197 | $13 | 6% |

| Method 2: Sizing Wire | 8 Hrs | $216 | $197 | $19 | 9% |

| Method 3: Pre-fab | 2 Hrs | $255 | $197 | $58 | 23% |

My guess is a lot of jewelers (probably most), order pre-fabricated shanks and settings and enjoy the time savings associated with Method 3 (after all, if you think about it, using Method 1 basically means you’re paying yourself less than $6 per hour to fabricate the components of the ring).

But let’s go back to that email from the start of this post: where the mill wants me to sell their pre-made jewelry.

When I started out here I was ordering raw materials from the mill and making handmade jewelry (the mill was solidly my vendor). Slowly, step by step, as we walk from Method 1 to Method 3, you can see how the mill lures jewelers to progressively easier methods for making jewelry – each step providing additional positive economics – until the jeweler is using Method 3, just a hop skip and a jump away from re-selling finished mass-produced jewelry.

The part of this I found most interesting was my emotional reaction to the proposition from the mill. I pride myself on making jewelry by hand, but at some point, between Method 1 and re-selling mass produced jewelry the “handmade” badge is lost.

Is it lost at Method 2? Method 3?

By blurring the line of what really is handmade and providing positive economics along the way, the mill has perfected their program of turning their customers into their re-sellers.

The really sad part of the story is when a jeweler starts re-selling mass produced jewelry – do their customers even notice the difference?

I found this whole system to be fascinating and applicable to lots of other businesses. I hope you enjoyed it too.